These are troubled times in the land of elephants. Back in early January, the Thai and international press reported on the alarming and tragic poaching of wild elephants from the Kaeng Krachan National Park in west Thailand, the country’s largest national park, which borders Myanmar.

What has evolved since is confusion, contradiction, misinformation, the arrests of poachers and wildlife officers, the investigations of elephant camps around the country including two internationally renowned sanctuaries, the confiscation of twenty-six elephants, and the recent news that one of those confiscated elephants has died.

This isolated incident may seem small when compared to the increasing number of elephants and other wildlife being massacred worldwide. An insatiable demand for ivory in Asia has led to an unprecedented surge of elephant poaching throughout Africa. And while we hope that at least some endangered Asian elephants, the females and tusk-less males, might be spared from the hunt for ivory, new reports show different. For it’s not only ivory that has value in the black market. Elephant meat and baby elephants are also on the poachers’ list. No wild elephant is safe. Not even in the protected national parks as is this recent case in Thailand.

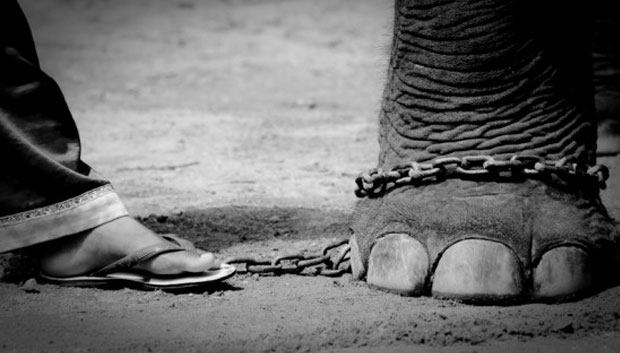

Elephants are an important animal in Thailand, traditionally, spiritually and economically. They are a national icon and, for better or worse, play a significant role in the tourism industry. It is for this very reason that the business of elephants ranks high in the national psyche and why the present controversy has had unsettling reverberations throughout the country. The issues surrounding elephants in Thailand are complex and with so many different stakeholders pitted against each other it is very difficult to get straight answers. Unfortunately the business of elephants is deeply mired in politics, legal loopholes, and profiteering.

There is a Thai law originally drafted in 1939 called the Draught Animal Act. The law and its ramifications are complex but very basically it requires all domesticated elephants must be registered by their owners with an ID card when they are eight years old. The registration law was developed during the time that elephants were used heavily in the logging industry. Logging was banned in Thailand in 1990 and the commercial use for elephants shifted to the tourism industry. As the demands for Asian elephants have increased in the tourism trade, both within Thailand and other countries, so has the need for elephants. But elephants don’t breed easily or quickly and in order to meet the demand they are captured from the wild to replenish the captive stock. This is against the law in Thailand and internationally. Baby elephants are the target, captured and sold into the tourist trade where they fetch a high price. By the time these wild-caught illegal elephants reach eight years old, if the owner even bothers to get registration papers they are either forged, purchased or passed on from registered elephants who have died. Although this law has been in place for decades, loopholes have enabled people to take advantage of the system which has proven to be profitable for a handful of business people who deal in elephants. So why the crackdown at this time?

When the poaching incident hit the news it was rumored that some wildlife officers were likely in on the deal. It was very difficult to find out exactly how many elephants were killed. The early reports were confusing – some said six elephants were killed, although the official report says two. Initially, it was said that the elephants were poached for their tusks – but then later reported that their trunks, tails and sexual organs were sold to restaurants who cater to “foreign” customers. To date, the consumption of elephant meat in restaurants in Thailand has not been verified. Eventually poachers and wildlife officers were arrested. It was later reported that not only were the elephants killed for their various parts, but baby elephants were snatched from their mothers – who were likely killed in the process – to be sold into a ring whose business is to train, sell and distribute wild-caught baby elephants into the tourist trade, a very lucrative business that has been going on in Thailand for years, which many people have known but few have done anything about.

Enter Damroch Pidech, Chief of the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Park Conservation (DNP). In reaction to the scandal, he publicly pledged to do something about the poaching and illegal trade of elephants. A nation-wide campaign was launched to investigate the origins of all captive elephants by enforcing the 1939 registration law, an effort that requires the cooperation and coordination between three government Ministries – not an easy feat in any country.

By the end of January reports started coming out about the illegal trade of wild-caught baby elephants from Thailand’s national parks and the wilds of Myanmar into the tourist business, with allegations of collaboration between officials and business operators – a so-called “elephant mafia”. Two of Thailand’s most out-spoken elephant and animal rights activists, Sangduen ‘Lek’ Chailert, and Edwin Wiek distributed press releases internationally about this activity. Shorty afterwards, their sanctuaries, Elephant Nature Park (ENP), and Wildlife Friends Foundation of Thailand (WFFT) respectively, were raided by the DNP officers. Reportedly ninety-nine animals, various species of rescued wildlife, were confiscated from WFFT on the grounds that the organization did not have the correct paperwork, while demands were made for the registration documents that were missing for eight of the thirty-five elephants owned by ENP. The social media around these incidents went viral and followers worldwide witnessed video clips of monkeys, gibbons and other animals being yanked from their cages and carted off by wildlife officers, while a small army of foreign volunteers passionately protested outside the gates of ENP in Chiangmai as government officers made three visits to the park and threatened to confiscate eight elephants unless the complete registration papers were presented.

What has ensued since has been international outcry, largely fueled by press releases by ENP and WFFT who claim that they were singled out in the investigations. Although they may not have had the chance to get their paperwork in order when the officers unexpectedly came to their doors, they claim that they have been targeted because they publicly spoke out about the corruption and wild-capture of baby elephants sold into the elephant business. In the latest reports, the elephants at ENP have not been confiscated, although tragically two of the gibbons taken from WFFT have died. This has certainly brought a lot of international attention to the issues in Thailand at present. But in the drama that has surrounded the emotionality of this outcry, the importance and potential benefits of this nation-wide shakedown have been overlooked.

It has not only been these activist’s sanctuaries that have been raided in Thailand. From Phuket in the south, to Kanchanaburi in the west, to Chiangmai in the north and the northeastern province of Surin – considered to be the hub of the elephant trade business – elephant camps are being inspected by DNP officers.

At this time of writing, 26 elephants without registration papers have been confiscated and impounded at the Thai Elephant Conservation Center (TECC), a government-run facility and elephant hospital. At the March 13th National Elephant Day symposium in Bangkok, the DNP Chief estimated that 10% of the captive elephants in Thailand are not registered. Exact numbers of elephants in Thailand are not easy to confirm but the numbers range between 1,200 wild elephants and 3,000 captive elephants. This suggests that there are approximately 300 elephants in captivity that are wild-caught from the national park jungles or captured and purchased in Myanmar and smuggled into Thailand to be resold. The DNP Chief estimates twenty to thirty wild baby elephants are smuggled into the Thailand tourist trade per year – some elephant conservationists and NGOs estimate more than one hundred.

As DNP officials continue to make their way around the countryside searching for un-registered elephants, the confiscation has created a major challenge for the veterinarians and mahouts whose job it is to care for the elephants now arriving at TECC. There were already some eighty elephants in residence at TECC as members of its elephant program. With the arrival of the new elephants now in federal custody comes the need for more facilities, food, water, and more mahouts. Properly trained mahouts are difficult to find in Thailand. In many villages it is a dying tradition, and many of these mahouts do not want to leave their homes in the rural areas to work in a government facility. For those who take the job, they need time to get to know the new elephant they are to care for – and for the elephant to trust and accept their new mahout. Most of the confiscated elephants have come from the Sai Yok Elephant Park in Kanchanaburi, and some from Phuket. Upon arrival at TECC, the elephants underwent a series of medical tests. Fifteen of the elephants were found to be unhealthy. Some were admitted into the Elephant Hospital; the others put into quarantine. At this time of writing one of the lead veterinarians at TECC has confirmed that eight elephants have tested positive in the screening process for a chronic respiratory disease, two have tested positive with a tetanus infection, and one of those elephants with tetanus has died.

Although the tourist camp owner of this deceased 17 year-old female elephant insists that she was not properly cared for at TECC, the tests and photos taken at the time of her arrival show otherwise. The veterinarian team states that all fifteen elephants were in poor health before they got there. Tetanus has a long incubation period and the likelihood that these two elephants already had the infection is very high. The other tetanus infected elephant is presently being treated and recovering. Although one elephant’s life has tragically been lost, this other elephant who is now under proper care at TECC may have a chance to survive.

Most people working with elephants in Thailand believe it is high time that the registration laws be enforced. What is questionable in the present shakedown process is the methodology undertaken. Does it make sense to confiscate and impound elephants when considering the costs, logistics, and risks to the elephants to be moved? Perhaps only in the cases where the elephants are not properly cared for. Although there is the law for elephant registration, there are no laws to enforce proper elephant care nor to prevent cruelty. Domesticated elephants are the private property of their owners who can do with the elephant whatever they choose.

At present, Thailand has its work cut out for itself to get its elephant business in order. No new rules have been passed as of yet but there are a lot of plans. The search for un-registered elephants is linked with the plan to create a DNA database of all the wild elephants in the forests. Any elephant without registration papers will be considered wild. All domesticated elephants are to be registered from the time they are babies with more detailed physical descriptions, micro-chipped and DNA recorded. The plan is that this comparative database would make it possible to tell the difference between wild and domesticated elephants thus preventing wild elephants to be smuggled into captivity. Meanwhile, in the background are the on-going and complex discussions about the need to create new laws for elephants that would put them in a category all their own, and ensure their proper care.

Yet amid the drama, the planning, and the investigations it’s the fate of the beloved elephants that is really at stake. In our work here as filmmakers we are trying to make sense of this situation and more importantly tell its story. For within this country we see the heart of the human-elephant relationship, a nation that is filled with good people with diverse points of view trying to save its elephants in a climate of socio-political change. At the centre of all these challenges is the love that the Thai people have for elephants. Where else can an elephant receive a Royal title from the King, or have a national holiday designated in its honor, or once be featured on the national flag?

The world is running out of elephants, both in the wild and in captivity. In Thailand it’s estimated that overall the population is decreasing by 3.5% per year – which means that in 30 years there will be no elephants left in the land of elephants. We can only hope that these efforts underway will help Thailand take care of its elephant business, not only as a nation that loves elephants but for the world that loves elephants too.